If we engage students in learning from and with each other through active discussion and group exploration of content;

then engagement will increase,students will become more self-directed learners, and acommunity of supporting learners will form.

Why it Matters

Schools have tended to see learning as an individual endeavor built on compliance and competition, and punctuated by awards, prizes, and levels of attainment (7). This is particularly prevalent in the United States, where the “prescription for success was and is a blend of pioneer spirit, self-assertion, individual ingenuity, and individual effort” (17). Although this competitive and individualized view of learning has long been criticized by education reformers (Elmore, Meier), scholars (Brown, Palinscar, Boaler), philosophers and theorists (Bruner, Dewey, Vygotsky, Malaguzzi), some educators still voice concerns that too much attention on the group will lead to a loss of the individuality of each child (11). However, rather than seeing the individual and the group as two opposing forces or contradictory approaches to teaching and learning, it is more useful to think of the symbiotic and dynamic relationship between the group and the individual. This recognizes that the individual grows in their relationship with the group without being subsumed by it. As Jerome Bruner eloquently stated, “mind is inside the head, but it is also with others.” (4. p. 87).

It is also useful here to make a distinction between the common use of group work or team assignments in which students produce a project or complete a task as a collective unit (often by merely dividing up the task) and the kind of true learning group, community of learners, or culture of thinking we are talking about here. The former is often a one-off task or experience whereas the latter is an ongoing commitment to the way the class operates. This kind of learning in, from, and with groups is situated within Vygotsky’s (16) sociocultural perspective, which theorizes individuals gradually internalize new concepts, psychological tools, and skills that are first externalized in their social settings they experience (14).

What makes a community of learners or an effective learning group? Jerome Bruner (4) identified four factors at play in communities of learners: a) agency, taking control of one’s learning, b) reflection, making the learning make sense, c) collaboration, sharing the human resources of all those involved in the mix of teaching and learning, and d) culture, the way of life and thought we construct, negotiate, and establish. In these factors we see a dynamic interplay between the group and the individual. Jo Boaler (3) identifies three necessary components of learning groups that promote high levels of achievement for all individuals and promote relational equity for all learners: a) respect for other people’s ideas, leading to positive intellectual relations, b) commitment to the learning of others, and c) learned methods of communication and support. When classroom functions as a true learning group, adults and children alike feel that they are part of something larger than themselves and has meaning beyond the individual (11). In learning communities, learners develop intellectually, socially, and academically.

Intellectual Development

Learning how to learn, growing intellectually, and learning to think are effective developed in a social context (5, 8). Through the process of explaining, defending and discussing with one another, children make use of their peers’ ideas as “thinking devices” which enable them to reflect on and transform their own thinking (17). When students learn alongside their more experienced peers, opportunities to “work together, brainstorm possibilities, pool knowledge and insights, conduct collective analyses, critique each other, and draw energy from a common goal” allows for deep learning to take place in a community of practice (10). Through talking to one another, students co-construct new knowledge and the “cognitive conflicts” that arise serve as the “power driving intellectual development” (12). Therefore, learning as a collective enterprise “build[s] on or extend[s], rather than replace, the work” of each student (11). Through working with others, students gain experiences that they would otherwise not have, including learning to “defend, negotiate and modify our ideas” (11).

Social Development

When learning is viewed as a collective endeavor and not an individual competition, students build their social and collaborative skills (19). Interdependence is a key component of communities of learning. As students share ideas and resources, they also assume a joint responsibility for learning (10). This creates a safe environment where students view one another as “allies” rather than competitors, thereby increasing engagement and academic achievement (15). When learning is a collective endeavor, students develop language and communication skills as well (18). As students work with their peers, they develop open-mindedness as they learn to “value the contribution of different methods, perspectives, and partially correct or even incorrect ideas” (2). Students also develop socio-emotional competencies, as they learn to ask probing questions to elicit their peers’ understanding of concepts, as well as through working with others across different ethnic and class backgrounds (2). Students also learn to respectfully communicate with others who have opinions different from theirs through interactions, like structured debates (13).

Academic Development

Employing peer instruction, Crouch & Mazur (6), found students more actively involved in the learning, more self-directed, and attaining higher levels of achievement and master when compared to traditional didactic instruction (6). Similar findings were reported in studies with school-aged students, where collaborative learning led to improved problem-solving outcomes (1). In Boaler’s study of secondary mathematics classrooms, she found heterogeneous grouped students who regularly worked collaborative (72% of class time spent in collaborative discussion) to solve conceptual mathematics outperformed students in traditional, tracked math classes (3). The key to their learning was that every student felt a commitment to the group’s learning and those that struggled were not viewed as pulling the class down but providing an opportunity to teach, explain, explore and build understanding within the community. The collaborative nature of learning also allows for students’ thinking to be made visible, as conversations reveal more information than written work (9). This provides an opportunity for teachers to collect and analyze data about students’ learning that are useful in informing their next steps in instruction (9).

What It Looks and Sounds Like

Of course, there is no one way that making learning and thinking a collective endeavor will look and sound. There is ample room for individuals to add their own creativity and stamp on things. The list below is a sampling of ideas that might be useful to advance your practice.

Engage students in collaborative note taking by using the +1 routine, which allows students to share and build off of one another’s ideas.

Provide opportunities for students to learn from one another and to share their expertise by using such as the jigsaw method, chalk talk, making meaning routine.

Have students talk to their neighbors or discuss in small groups before asking individuals too share in the larger whole-group setting. This allows times for both introverts and extroverts to develop their ideas. This may occur through, Think-Pair-Share, 1-2-4 All, Sketch Studio for non-written idea gathering or Chat Stations. All these formats allow students the chance to develop their ideas and learn from others in a less public space, which may facilitate quieter students having more confidence to share. Remember, the first person to share in a group often sets the tone for what will follow so giving students think and processing time can often assure a better start to a discussion.

Share, model, and promote “ice cream cone” more than “popcorn” conversations. In a “popcorn” mode, people “pop” or speak, when they are moved to. This often produces disconnected talk and ideas. In an “ice cream cone” conversation, people build on or stack ideas onto other’s contributions to go deeper and explore ideas.

Make sure group tasks require interdependence among team members. If a task can be completed by dividing it into parts and assigning jobs to individuals, then it is unlikely to produce much learning.

Refrain from making comparisons among students or setting up structures that lock students into a track or pecking order that prejudges their abilities, motivations, and interests.

Encourage students to help one another, rather than view one another as competition.

Create displays that highlight the contributions of a diverse range of students to the group’s learning and collective understanding rather than showcases of “best work” produced by individuals.

Provide structures, such as Ladder of Feedback or SAIL, and opportunities for peer feedback where students are able to take turns giving and receiving feedback on works in progress.

Document the group’s learning that shows how our understanding develops through the contributions of everyone. Documentation, recording, drawing makes conversation tangilbe and easier to follow (27).

Set ground rules to support students’ participation through establishing discussion norms, signaling the goals of the discussion to allow students to anticipate the kind of contributions that are relevant to and appropriate for that particular discussion.

Teach, model, use, and reinforce accountable talk to help students effectively engage in meaningful and respectful conversations that are mutually beneficial to both speaker and listener.

Utilize “vertical non-permanent surfaces” like “whiteboards, blackboards, or windows” to allow students to make their thinking visible to each other and to you. This strategy helps to focus the attention on the conversation., When learners broadcast their writing and make it available for monitoring by other members of the group, this encourages a joint focus of attention. (20)

Ensure that the physical set-up of the classroom allows for collaboration. A flexible design such that classroom furniture can be moved around can facilitate interactions among students and teachers can easily move around as well. (8)

Create tasks that provide multiple entry points and allow for multiple ways for students to demonstrate competence. The task should be “open-ended, allowing for multiple representation and have several possible solution paths”. For instance, the task could ask for different strategies to solve a problem. Ask students to show the connections across the strategies to stretch them beyond what they already know. (8, 20, 21)

Engage students in group analysis, problem-solving, or experimentation settings in which understanding is built within the group through their discussion and exploration. Hold students individually accountable for their group learning through individual assessments of learning (e.g., individual report / reflection) and/or using assessment of individual effort to adjust grades.

Form heterogeneous ability groups. This would allow the novice student to learn from the more advanced student. The more advanced student will also benefit from teaching others. This also avoids a situation where more advanced students group together while a less ideal learning environment forms among the other students. (23)

Talk about the group’s questions, insights, understandings rather than only that of individuals.

Model what active listening looks like and how to give effective feedback.

Discuss what types of interactions are useful and which are not in a group setting.

Teach students how to give constructive feedback with actionable steps rather than surface-level praise, and comments or facial expressions that aren’t helpful.

Teach, model, and use clarifying and probing questions; focus on their role in gaining understanding of others and of helping them to advance their understanding.

Have students set group norms at the beginning of group formation (See Exhibit 1 for norm-setting protocol). This can set a strong foundation for effective team processes as students are held accountable for their behavior and it can also foster a safe learning environment for all

Have students revisit their group norms regularly and revise the norms if necessary. This would be important to help students monitor their own behavior in a group discussion and the students can develop a common language to discuss how they are working together. Students can start by discussing evidence how well the group thinks each norm is being followed. (24)

Observe individual students on their social skills when interacting with their group members and give them individual feedback. This has been found to improve relationships within the group (25).

Observe students when they are working in groups and be intentional about “assigning competence to low-status students”. These are the students who are perceived to be less academically inclined or less popular. When these students demonstrate competence on an important intellectual ability, publicly describe what the student has done well and explain why this is an important resource for the group.’ This would be important in modifying status effects to promote equity (26).

Name and notice when and how students learn from others, build on one another’s ideas, draw others into conversation.

Reflecting on Your Teaching

These questions are meant to push your thinking beyond where you are currently. Perhaps they might even make you a bit uncomfortable. Pick a question or questions that will help you better understand the effects of your actions, critically reflect on them, provoke additional questions, and/or help you think about future actions and possibilities. If you find yourself merely explaining what you currently are doing, chances are you might be reporting more than reflecting. Consider selecting another prompt that might take you deeper into examining your practice.

How am I teaching and supporting students in having rich, fruitful, and respectful conversations in my class?

Where, when and how do I provide students feedback on their participation in conversation?

How do I ensure all voices are heard in discussion and avoid gender, racial, perceived ability, or extrovert bias when I call on students?

What opportunities do students have to exchange and share knowledge?

In what ways am I modeling what it means to be a good listener, and what it means to treat others with respect and consideration?

In group settings, what am I noticing with regards to students asking one another task-focused questions, providing justification for statements they have made, considering more than one possible position before coming to a decision, eliciting the opinion of everyone, and seeking agreement before taking action? How can I teach, support, and reinforce these practices?

How might I adapt an upcoming task so that it affords more than one starting point, requires more than one solution path, and makes thinking and learning visible?

In thinking about an upcoming group task, does it require positive interdependence and individual accountability (e.g. individual report written at the end of the project)?

Where, when, and how am I providing thinking time before launching into group discussions? What am I noticing about the difference this makes to both who contributes and quality of those contributions.

How is space in the classroom utilized to facilitate student discussions? Do students have the option to move and move somewhere other than their desks? Are there flipcharts / poster boards / whiteboards available to students?

In what ways are students on their individual learning as well as progress as a group?

What routines and structures do I use to facilitate students’ group discussion, problem solving, and learning? What makes these routines effective? Who are they not working for?

How do I make use of documentation to capture group learning? Where and how might I do more of that?

How do I prepare my students to work collaboratively with one another? What needs further reinforcement?

Can my students describe what makes an effective learning group and group discussion?

Where, when, and how do I ensure that students in my class work across different ability levels, ethnic groups, gender lines, and friendship groups?

Using Quick Data to Inform Your Efforts

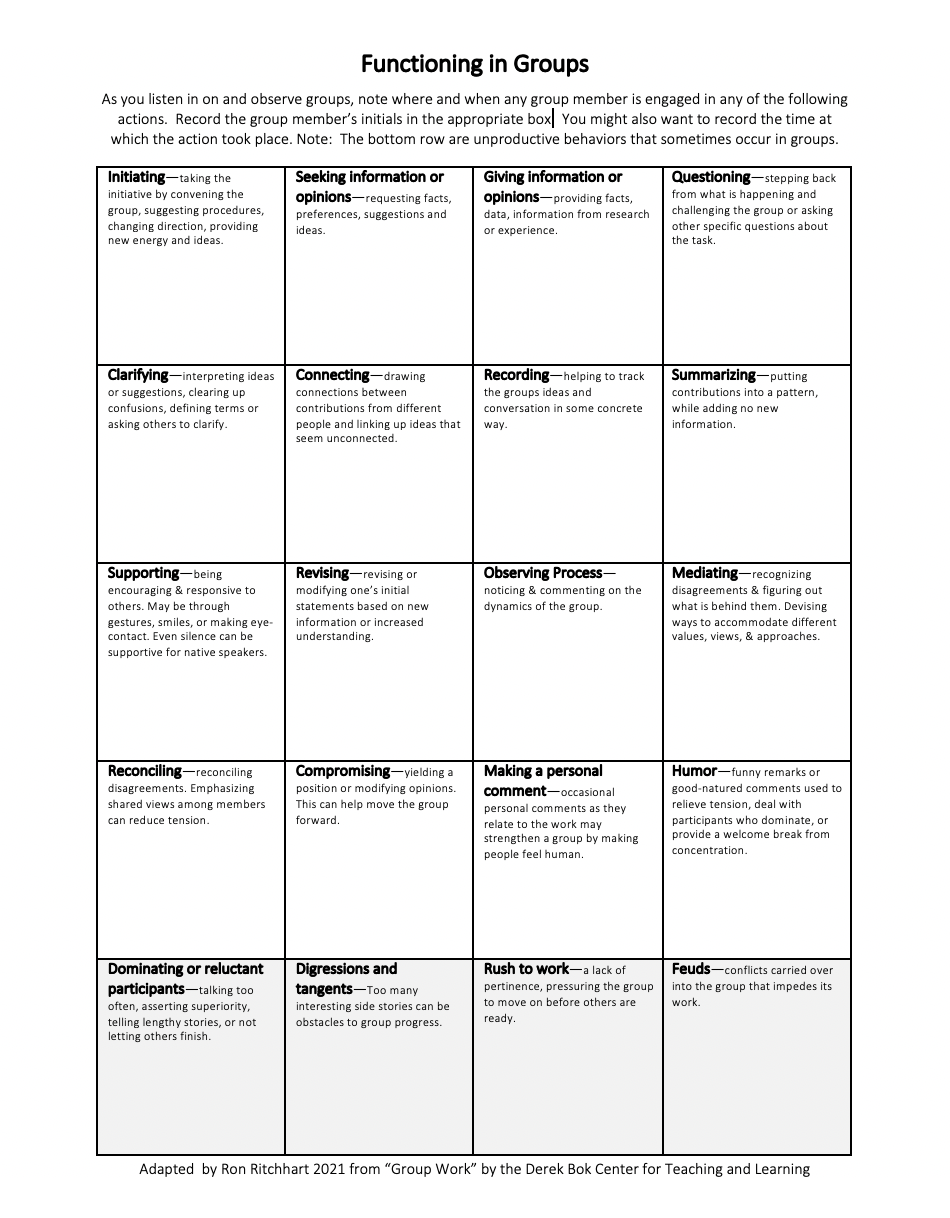

Use Functioning in Groups observation checklist to identify the types of behaviors in which members of a learning group engage. The checklist could be used when students are working in small groups or during a whole class discussion. If used to track a whole-class discussion, not all of the behaviors are likely to be observed.

Questions to Consider from the Quick Data:

What interesting or surprising details do you notice?

What questions or reflections does the data evoke?

What possible factors contribute to students style of interaction?

What actions were most prevalent? Which were least observed? Why do you think this is so?

What skills/actions of group functioning need more attention, clarification, and practice? How will you do this?

How might you share the data back with the students?

Connection to the 8 Cultural Forces

Interactions Learning in, with, and through collaboration with others means that teaching and developing positive was of interacting in large and small group settings is key. We can’t expect students to simply come to our classrooms prepared to productively engaged with others. This entails establishing a culture of respect with attention to both community and agency. When everyone feels responsible for each other’s learning, learning for everyone increases (3). Students need to see one another as important resources in the classroom and actively seek help from others beyond the teacher.

Routines. Don’t expect students to know how to interact, collaborate, listen, give feedback or even talk to one another appropriately and effectively at the beginning of the year. Use routines and protocols that help students learn these behaviors. Set norms for group learning. Revisit these norms often to check to see how they are working. Think-Pair-Share, 1-2-4 All, Sketch Studio for non-written idea gathering or Chat Stations are all useful structures for collaboration.

Opportunities. Create group worthy tasks that focus on the co-construction of understanding, group interdependence, as well as individual accountability. Such tasks generally address complex problems, issues, or projects and have several possible solution paths. They demand extensive interaction and discussion and cannot be completed through a divide and conquer strategy in which individuals merely paste their contributions on to one another.

Time. Teachers invest time in building students’ interactive skills early in the year by explicitly teaching and debriefing group interactions. They deal with group conflicts immediately by teaching students how to solve problems for themselves.

Modeling. Through our interactions with students we model how to treat one another and thus build community in our classroom. Our students are always looking to us as the exemplars. Fish bowl observations allow us to formally model group interactions and make the implicit explicit. (See this example of a teacher introducing the Ladder of Feedback using the Fish Bowl technique).

Language. Many conflicts and misunderstandings occur through misinterpretation of what others are trying to communicate. Learning the language of listening, accountable talk, the language of feedback, and how to ask clarifying and probing questions, are helpful tools to avoid such miscommunication. Fish Bowl observations can be a tool for modeling such language moves.

Environment. The physical environment of the classroom and school must be set up in a way that facilitates students learning in, from, and with groups. Create flexibie spaces that can easily be reconfigured into campfires, watering holes, and caves as needed. Desks in roles communicates that learning is a solo endeavor in which one merely listens to and watches the teacher.

Expectations. Learning in, from, and with groups is the expectation of the class not the exception. Students come to expect that they learn through active discussion, that their ideas contribute to the whole, that they are not in the classroom as solo agents but as collective partners.

“Real learning does not happen until students are brought into relationship with the teacher, with each other, and with the subject. We cannot learn deeply and well until a community of learning is created in the classroom.

”

“If you want to go quickly, go alone. If you want to go far, go together.

”

“[A community of learners] relies on the development of a discourse genre in which constructive discussion, questioning, querying, and criticism are the mode rather than the exception. In time, these reflective activities become internalized as self-reflective practices and foster children’s growing theories of learning”

“Work together, brainstorm possibilities, pool knowledge and insights, conduct collective analyses, critique each other, and draw energy from a common goal.”

“in a school or classroom· functioning as a learning

group, adults and children feel like they are part of something larger than themselves that has meaning beyond what each individual has learned.”

Resources

Video

Interview

Podcast

Article

Blog

Research

3 minutes

Making the Most of Classroom Talk

In this short video Neil Mercer ( a leader in dialogue and “Oracy”) explains why classroom talk matters, how it relates to learning outcomes, and how teachers can nurture productive exploratory dialogue. He outlines the key features of interactive vs authoritarian dialogue. (2021)

30 Minutes

Making Cooperative Learning Work Better

In this podcast with an accompanying article, Jennifer Gonzalez shares possible solutions to the common problems that arise when cooperative learning takes place. This includes uneven student contributions, interpersonal conflicts, off task behavior and student absences. (2020)

10 pages

Breaking the cycle of mistrust: Wise interventions to provide critical feedback across the racial divide

This article, put together by the Derek Bok Center for Teaching and Learning at Harvard is intended to be short and simply written guide for students who are working in groups, but who may not be very interested in too much detail. It also provides teachers (and students) with tips on assigning group projects, ways to organize groups, and what to do when the process goes awry. (2014)

6 minutes

Getting students thinking and engaging through small-group discussion

In discussion-based classes, especially large ones, it is difficult to ensure that all students have a chance to verbalize their thinking and receive feedback on their ideas. Incorporating small-group discussion is a low-stakes way of ensuring that all students have the opportunity to actively engage with course material and their peers. In this video interview, Todd Rakoff breaks students up into small groups to apply abstract legal principles to a concrete problem. Students discuss in small groups before participating in a whole class discussion, where Rakoff solicits insights and synthesizes students’ perspectives. Links to research and tools (2015)

6 pages

The Big List of Class Discussion Strategies

In this article, Jennifer Gonzalez shares 15 different formats for structuring class discussions. These strategies have been categorized into three groups: higher-prep strategies, low-prep strategies and ongoing strategies. These different strategies seek to make learning more engaging, equitable and challenging for students. (2015)

6 pages

The Case for Dialogic Learning

In this blog, Barbara Bleiman follows up on an online event, Dialogic Learning - Research, Principles and Practices - with a summary of the 7 key points made by different speakers. Backed up by links to relevant research, both past and present, she makes a powerful case for the necessity of finding room for interactive dialogue to take place in all of our classrooms. (2021)

8 Minutes

Two better ways to have group conversations

The Conversation Factory podcast focuses on changing conversations with the tools of design. In this 3rd Installment of the “Think Alone, Think Together” series , Daniel Stillman walks viewers through six ways of shape group conversations in both a video and accompanying article. (2018)

15 pages

Transforming Schools Into Communities of Thinking and Learning About Serious Matters

In this article, a program of research known as Fostering Communities of Learners is described. This program served inner city students from 6 to I 2 and was successful at improving both literacy skills and domain-area subject matter knowledge by building on young children’s emergent strategic and metacognitive knowledge, together with their skeletal biological theories. The program leads children collectively to discover the deep principles of the domain and to develop flexible learning and inquiry strategies of wide applicability in a group. (1997)

8 pages

How can teachers maximize student learning gained by group work?

Researchers Nancy Frey, Doug Fisher, Michael Fisher, Dr. Laura Greenstein, Debbie Zacarian, Michael Silverstone, and Cindy Terebush weigh in on the elements that make for productive group work. Specifically, they argue that to maximize group work, teachers need to make it metacognitive (2019).

3 pages

Classroom Dialogue: Does it really make a difference for student learning?

British Researchers Christine Howe, Sarah Hennessy, and Niel Mercer provide a short overview of research that highlights the effective qualities of classroom dialogue that have been shown to produce stronger learner outcomes on traditional learning measures. These include students elaborating and building on one another’s ideas, Questioning and challenging other students, and participation. (2023)

27 pages

Building Thinking Classrooms: Conditions for Problem Solving

Using a narrative and highly readable style, researcher Peter Liljedahl of Simon Fraser University tells the story of how a series of failed experiences in promoting problem solving in the classroom led first to the notion of a thinking classroom and then to a research project designed to find ways to help teacher build such a classroom. Results indicate that there are a number of relatively easy to implement teaching practices that can bypass the normative behaviors of almost any classroom and begin the process of developing a thinking classroom. This article is a forerunner to his highly popular book and provides a good overview. (2016)

4 minutes

Improving Problem Solving in Math Through Accountable Talk & Asynchronous Video

Kickemuit Middle School Math Teacher & Digital Learning Team member Jen Saarinen discusses how students use FlipGrid to engage in accountable talk as a strategy to improve their problem solving skills in Math. (2016)

6 pages

Promoting respectful learning

Professor Jo Boaler of Standford University, discusses how students in an urhan high school learn to appreciate diversity and respect multiple viewpoints as they help one another succeed in mathematics. (2006)

5 minutes

Using jigsaws to facilitate small-group discussions

“Jigsaw” discussions are an efficient and student-centered way to get your class familiar with many different texts or materials. By dividing students into groups that each work with different content, then having individuals from each group teach that content to their peers, you can encourage students to build on each others’ ideas and find patterns throughout their course content. In this video interview, Tina Grotzer describes how she uses jigsaws to facilitate in-depth discussion in her classroom. Multiple links to other guides and tools for using the Jigsaw, especially in science. (2010)